Want to End Poverty? Tackle inequality First - Erik Solheim

There is broad support for the idea to set a global goal to end extreme poverty by 2030, as recent international conferences such as the World Economic Forum’s Annual Meeting in Davos and the ongoing consultations on the post-2015 agenda show. Great progress has been made in poverty reduction, but ending poverty with the current growth pattern would be difficult and harmful to the environment. The global momentum for an ambitious goal on poverty reduction is strong, but some question whether it is possible to end poverty while growing in an environmentally, socially and economically sustainable way. There are very good reasons to side with the optimists in this debate – but only if we manage to break through one major obstacle: inequality.

There is broad support for the idea to set a global goal to end extreme poverty by 2030, as recent international conferences such as the World Economic Forum’s Annual Meeting in Davos and the ongoing consultations on the post-2015 agenda show. Great progress has been made in poverty reduction, but ending poverty with the current growth pattern would be difficult and harmful to the environment. The global momentum for an ambitious goal on poverty reduction is strong, but some question whether it is possible to end poverty while growing in an environmentally, socially and economically sustainable way. There are very good reasons to side with the optimists in this debate – but only if we manage to break through one major obstacle: inequality.

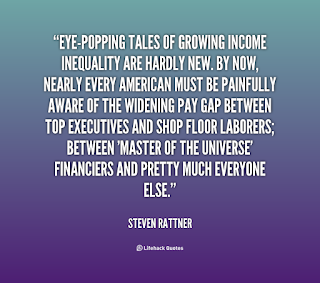

Income inequality within countries has been on the rise in most of the world’s regions over the past decades. So-called household income inequality, as measured by the population weighted average of the Gini index, increased by 11% in low- and middle-income countries and by 9% in high-income countries from the early 1990s to the late 2000s. Highly unequal societies are emerging, and recently the international community has given heightened attention to this issue: Statesmen such as Barack Obama, economists such as Joseph Stiglitz, religious leaders including Pope Francisand international organizations such as the UNDP and the OECD have declared that tackling inequalities a core priority for our generation. While there are plenty of convincing ethical, ideological, and political arguments against inequality, fighting it also is of utmost importance for the global goal to end poverty. Today, 1.2 billion people live on less than US$ 1.25 a day – in what we call “extreme income poverty”. More than 70% of them live in middle-income countries where the gross national income averages between US$ 1,036 and US$ 4,085 per citizen per annum. This astonishing figure demonstrates that in many countries a lot of people have not yet benefited from their country’s stronger economic performance. If these countries succeeded in distributing income more evenly and grew in a more inclusive way, we would take a huge step towards zero on extreme poverty.

Several countries show that strong economic growth does not have to be accompanied by rising inequalities. Brazil, which grew strongly over the past decade, can serve as an instructive example. In the early 2000s, Brazil began to implement a model of development that focused on social policy. Projects such as the Bolsa Família (a family stipend programme), which transferred cash to poor families in exchange for enrolling children in school and ensuring regular medical checks, as well as a rural pension scheme (previdência rural) and public services for those who need them most were implemented. The policies were highly successful in lifting millions of Brazilians out of poverty: the incomes of the poorest 20% increased seven times as fast as the top 20% and Brazil became one of the most successful countries in poverty reduction. The example of Brazil corroborates an overall observation that can also be made in countries such as Peru and Ethiopia: Effective policies that reduce inequality ensure the inclusiveness of growth and lift people out of poverty. Social protection, redistributive cash transfers, and the provision of public education, health, and other services have helped these countries to lower inequality, against the global trend, and have proven to be highly effective and efficient tools to reduce poverty. Importantly – and contrary to what has often been assumed – policies that reduce inequality, if they are well designed, do not curb but can even contribute to growth as has been the case in the countries mentioned.

Several countries show that strong economic growth does not have to be accompanied by rising inequalities. Brazil, which grew strongly over the past decade, can serve as an instructive example. In the early 2000s, Brazil began to implement a model of development that focused on social policy. Projects such as the Bolsa Família (a family stipend programme), which transferred cash to poor families in exchange for enrolling children in school and ensuring regular medical checks, as well as a rural pension scheme (previdência rural) and public services for those who need them most were implemented. The policies were highly successful in lifting millions of Brazilians out of poverty: the incomes of the poorest 20% increased seven times as fast as the top 20% and Brazil became one of the most successful countries in poverty reduction. The example of Brazil corroborates an overall observation that can also be made in countries such as Peru and Ethiopia: Effective policies that reduce inequality ensure the inclusiveness of growth and lift people out of poverty. Social protection, redistributive cash transfers, and the provision of public education, health, and other services have helped these countries to lower inequality, against the global trend, and have proven to be highly effective and efficient tools to reduce poverty. Importantly – and contrary to what has often been assumed – policies that reduce inequality, if they are well designed, do not curb but can even contribute to growth as has been the case in the countries mentioned.  Such policies can promote skills development, boost employment and increase economic resilience. OECD research also shows that more equal societies have greater upward social mobility and can guarantee more equality of opportunities, contributing directly to economic growth. At the same time, equality has been found to contribute to social cohesion while inequality often tends to lead to fragility. During the past decades, most fragile countries did not make much progress in achieving development goals and reducing poverty. While today almost a third of the world’s poor live in fragile states, this figure will likely rise to 50% within the next years. To lift these people out of poverty, inequalities must be tackled to promote social cohesion and stability in the fragile countries in which they live. Non-inclusive growth, on the other hand, may eventually compromise itself by triggering social and political unrest and crises.

Such policies can promote skills development, boost employment and increase economic resilience. OECD research also shows that more equal societies have greater upward social mobility and can guarantee more equality of opportunities, contributing directly to economic growth. At the same time, equality has been found to contribute to social cohesion while inequality often tends to lead to fragility. During the past decades, most fragile countries did not make much progress in achieving development goals and reducing poverty. While today almost a third of the world’s poor live in fragile states, this figure will likely rise to 50% within the next years. To lift these people out of poverty, inequalities must be tackled to promote social cohesion and stability in the fragile countries in which they live. Non-inclusive growth, on the other hand, may eventually compromise itself by triggering social and political unrest and crises.

Of course, inequality-reduction policies should go hand in hand with the mobilization of additional domestic resources. Our data and success stories such as South Korea, China and Vietnam suggest that there is a vast untapped potential for greater tax revenue generation in many developing countries. Policies and international initiatives focusing on better tax policies and collection systems, on multinational enterprises paying a fair share, and on illicit financial flows are among the most promising instruments in this regard. It is a reason for optimism that many extreme poor already live in countries where poverty could be ended if at least moderate additional shares of their GDPs could be mobilized to be spent on inequality reduction. All this unmistakeably demonstrates that tackling inequalities is key to poverty reduction and sustainable development. Only if the world economy grows in an inclusive way will ending poverty be possible with sustainable growth patterns. The post-2015 agenda should account for this and include global goals, targets, and indicators on inequality reduction. If we are serious about ending poverty, we should make the fight against inequality a core priority for the years to come.

Author: Erik Solheim is Chair of the OECD Development Assistance Committee; Original Article is here

The emerging world’s inequality time bomb -Nathan Eagle

Oxfam’s recent estimate that 85 multibillionaires have accumulated fortunes greater than the wealth of the world’s poorest 3.5 billion people implies an uncomfortable situation for governments worldwide: economic disparity is worse today than at any other point in history. Considering the overall condition of our world economy, this seems surprising. According to nearly every indicator, the income gap between each country on the planet is shrinking, as dynamic markets in Asia, Africa and Latin America begin to catch up (and even surpass) those of Europe and North America. But within societies, the difference between the richest and poorest has never been more apparent. On the Gini coefficient, 0 represents a state of perfect economic equality, and 1 represents total inequality. The United Nations rates coefficients greater than 0.4 to be indicative of dangerous levels of inequality. According to the most recent data available from the World Bank, nine G20 economies (Argentina, Brazil, China, Mexico, Russia, South Africa, Turkey and the United States) have already passed the 0.4 threshold, implying dangerous levels of inequality. Of the remaining major economies, only Japan and Germany have coefficients of less than 0.3 (no data is available for Saudi Arabia).

Oxfam’s recent estimate that 85 multibillionaires have accumulated fortunes greater than the wealth of the world’s poorest 3.5 billion people implies an uncomfortable situation for governments worldwide: economic disparity is worse today than at any other point in history. Considering the overall condition of our world economy, this seems surprising. According to nearly every indicator, the income gap between each country on the planet is shrinking, as dynamic markets in Asia, Africa and Latin America begin to catch up (and even surpass) those of Europe and North America. But within societies, the difference between the richest and poorest has never been more apparent. On the Gini coefficient, 0 represents a state of perfect economic equality, and 1 represents total inequality. The United Nations rates coefficients greater than 0.4 to be indicative of dangerous levels of inequality. According to the most recent data available from the World Bank, nine G20 economies (Argentina, Brazil, China, Mexico, Russia, South Africa, Turkey and the United States) have already passed the 0.4 threshold, implying dangerous levels of inequality. Of the remaining major economies, only Japan and Germany have coefficients of less than 0.3 (no data is available for Saudi Arabia).

Beyond the G20, the World Bank lists 29 economies in sub-Saharan Africa with coefficients above 0.4, as well as 19 in Latin America, five in East Asia and five in the Caribbean. Where crossing the 0.4 threshold once represented a state of gross inequality, it is now the status quo for much of the world. Left uncorrected, disparity at this level can have serious, negative consequences. Social unrest of the type that we are seeing in Brazil is directly linked to the extra financial burden placed on taxpayers from the building of stadiums, hotels and associated infrastructure for the 2014 World Cup. Following months of dissent, last summer’s 50-cent bus fare hike in Rio de Janeiro ignited a series of violent protests that have continued into this year. A Jana poll run in February 2014 offered some insight into the public mood. As a poll of Brazil’s middle-class mobile Internet users, it should represent the opinions of those enjoying the benefits of Brazil’s growing economic might. However, the feedback that we took from our panel painted an overwhelmingly negative picture. Among respondents, 93% recognize economic disparity as a serious problem in Brazil. Furthermore, 77% believe Brazil’s tax system is unjust; and 67% believe to some degree that the economic system in Brazil favours the wealthy.

This situation is not unique to Brazil. The same poll of similar demographics in India, Indonesia, Kenya, Mexico, Nigeria, the Philippines, South Africa and Vietnam offers insight into perceptions of wealth distribution and the steps that people are willing to take to address it. Results across all nine markets echoed the dissatisfaction of our Brazilian respondents. An average 82% recognize economic disparity as a serious problem in their country. An average of 61% feel that the taxation system in their country is unjust. If these responses are representative of the greater public, we can draw two conclusions. First, that people across the world can see and understand the economic disparity around them; and second, that they don’t believe the economic system in which they live can offer a tax-driven solution. This level of disenfranchisement should be of great concern to those in power. Here’s why: when people become marginalized, they take to the streets. Indeed, our respondents are already familiar with protest. An average of 33% reported that they have taken part in demonstrations against political or business organizations. In India, Indonesia and Kenya, that number is as high as 45%. These people are the world’s emerging middle class, the “next billion” consumers. If they are to be the major growth engine of our global economy, they must share in the benefits of economic growth. If not, it is likely that we will see them turning against the interests of the state in favour of their own well-being.

This situation is not unique to Brazil. The same poll of similar demographics in India, Indonesia, Kenya, Mexico, Nigeria, the Philippines, South Africa and Vietnam offers insight into perceptions of wealth distribution and the steps that people are willing to take to address it. Results across all nine markets echoed the dissatisfaction of our Brazilian respondents. An average 82% recognize economic disparity as a serious problem in their country. An average of 61% feel that the taxation system in their country is unjust. If these responses are representative of the greater public, we can draw two conclusions. First, that people across the world can see and understand the economic disparity around them; and second, that they don’t believe the economic system in which they live can offer a tax-driven solution. This level of disenfranchisement should be of great concern to those in power. Here’s why: when people become marginalized, they take to the streets. Indeed, our respondents are already familiar with protest. An average of 33% reported that they have taken part in demonstrations against political or business organizations. In India, Indonesia and Kenya, that number is as high as 45%. These people are the world’s emerging middle class, the “next billion” consumers. If they are to be the major growth engine of our global economy, they must share in the benefits of economic growth. If not, it is likely that we will see them turning against the interests of the state in favour of their own well-being.

Author: Nathan Eagle is Co-Founder and Chief Executive Officer of Jana, a World Economic Forum Technology Pioneer company. The Original Article is free here

No comments:

Post a Comment